It's on Canal Street, next to Miami Jacobs.

It's on Canal Street, next to Miami Jacobs.According to the caption in the Lutzenberger collection:

"...The building on the right was Chambers Canal Depot. It was built in 1850 and was still standing in 1935. All merchandise was received and shipped from this point between First and Second Streets."

Assuming Lutzenberger is correct, about the date and use. at 1850 this was one of the very last buildings of the canal era, when the canal was the primary trade route to and from Dayton. In 1851 the first railroad arrived (coming in to town about a block and half north of here), marking the start of a new transportation era. The canal basin was directly across the street from this structure.

Assuming Lutzenberger is correct, about the date and use. at 1850 this was one of the very last buildings of the canal era, when the canal was the primary trade route to and from Dayton. In 1851 the first railroad arrived (coming in to town about a block and half north of here), marking the start of a new transportation era. The canal basin was directly across the street from this structure.As a commission and forwarding house this structure was directly related to the canal trade as this business acted as middleman between farmers and other producers and merchants outside of Dayton. This middleman trade was the first driver of local economic growth during the keelboat and flatboat era, were Dayton merchants assembled the agricultural surplus from area farmers and floated it down to New Orleans for sale, returning by land (before steamboat service) possibly via the Natchez Trace.. Mercantile houses also brought raw and finished goods overland from the east via wagon, flatboat, and pack horse, later when the roads were opened, via freighter wagon.

After the Miami and Erie canal opened Cincinnati and the canal replaced New Orleans and the river system as the trade route and goal, but the middleman role remained as an intermediary between the local and outside market.

After the Miami and Erie canal opened Cincinnati and the canal replaced New Orleans and the river system as the trade route and goal, but the middleman role remained as an intermediary between the local and outside market.So, as the last structure in Dayton directly related to the canal and the canal trade which helped build the city one would think some sort of landmark designation is in order

There is some architectural significance, too, as there are very few (if any) commercial structures surviving in Dayton from the 1850s, with this clean neoclassical style.

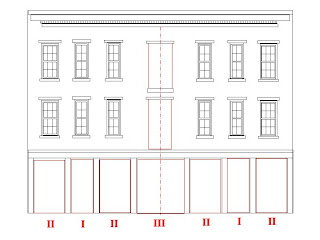

The façade composition is symmetric, but note the differing methods of establishing rhythm on the façade, with the ground floor having this paired pattern,

The façade composition is symmetric, but note the differing methods of establishing rhythm on the façade, with the ground floor having this paired pattern,II-I-II-III-II-I-II

Which controls the upper portion of the façade via centerline, but the upper part having a symmetric yet different rhythm

Which controls the upper portion of the façade via centerline, but the upper part having a symmetric yet different rhythmII-I-I-III-I-I-II

The center openings appear to be somewhat altered as they can be barely seen on this old image to be maybe more open, permitting things to be lifted up into upper floors for storage

The center openings appear to be somewhat altered as they can be barely seen on this old image to be maybe more open, permitting things to be lifted up into upper floors for storage Some details, showing the stonework, window frames (upper floors original?) and cornice details" The ground floor was probably bricked-in in at some later date, as one can imagine the lower opening being open to the canal landing for ease in hauling

Some details, showing the stonework, window frames (upper floors original?) and cornice details" The ground floor was probably bricked-in in at some later date, as one can imagine the lower opening being open to the canal landing for ease in hauling

Clearly this building has neoclassical features, in the façade composition and in the cornice detail (assuming they are original), as one does not see the heavy Italianate corbelling and volutes in later cornice treatments.

Clearly this building has neoclassical features, in the façade composition and in the cornice detail (assuming they are original), as one does not see the heavy Italianate corbelling and volutes in later cornice treatments.

And the building bears a family resemblance to other older, but now lost, Dayton structures.

The building is not threatened as it is the home of an active business. So perhaps not a preservation issue as much as a recognition issue.

The building is not threatened as it is the home of an active business. So perhaps not a preservation issue as much as a recognition issue.(Year of construction 1850? Historical trivia for that year: Zachary Taylor died in office that year, replaced by Millard Fillmore. Compromise of1850 to deal with slavery in the recent aquistions from Mexico, and Califorinia joins the Union...one of the few states to do so without going through territorial government).