Not the mall itself, but the area around it. It’s cool to bash the Dayton Mall area as ugly, congested, sprawl, blah, blah, blah, and its becoming cool to make subtle racial/social class innuendo about the clientele (“Dayton Mall is ghetto”) since this the only mall area to have transit connections to the city.

However, the place is really pretty rich in detail as a suburban shopping district, being more a true downtown than other mall areas, due to the mix of businesses here and peculiar way the place built-out. One can find pool halls, girly joints, bars, a drive-through, ethnic restaurants and food places, and so forth in the area. There’s a bit more “space” for non-standard, non-chain things than at first glance, and for a wider variety of shoppers.

A big contrast is the much newer Fairfield Commons area, where its all very planned and sanitized, no messy vitality there at all. Superficially similar these mall districts couldn’t be more different. One doesn’t here nowhere near the bashing of this mall district, but the implications of Fairfield Commons area is much more sinister, especially the way the poor are excluded due to lack of transit.

Daytonology will be blogging in-depth on the two mall areas over the summer, exploring their different characteristics.

Sunday, April 27, 2008

Dayton's Court

Courts are pedestrian streets, built in the early 20th century, and are pretty rare. Dayton has one, Audubon Court, in Lower Dayton View. Lets take a look.

Basically the houses face each other over a lawn and walkway instead of a street. Parking would be in rear garages.

Apparently in the past there was some planning here, as a walkway connects the court with a park in the next block, visible in the distance. An illustration of the possibility of working pedestrian paths and walks into a neighborhood:

Apparently in the past there was some planning here, as a walkway connects the court with a park in the next block, visible in the distance. An illustration of the possibility of working pedestrian paths and walks into a neighborhood:

Two contrasting approaches to front yards: chain link & no chain link

Two contrasting approaches to front yards: chain link & no chain link

Louisville Courts

Demonstrating what courts look like if the landscaping and houses are maintained, here are five of the 17 Louisville courts (there were 20 at one time).

Louisville might have the largest concentration in the US, though I hear Richmond, VA has a few. The Louisville examples are all considered “streets”, have city street signs, and are shown as such on maps. There are a variety of housing styles on Louisville courts: bungalows (big and small), foursquares, apartment buildings, Victorian, even a court of shotgun houses.

Two South End Courts.

These are in Louisville’s “South End” (roughly equivalent to Dayton’s Belmont), in the Southern Heights neighborhood. You’ll note that people are not chain-linking their front yards; the central court space is being treated as a continuous lawn. Maybe not exactly comparable to Audubon as the court space here is pretty wide.

Ouerbacher Court.

Ouerbacher Court.

This is a “private” court as it is secured by a gate from the street (of the 17 this is the only private one). There is a second court opening into this one at mid block, so an example of a”system” of courts. Note again, lack of fencing in the front yards, with the court being treated as a communal open space. In dimension this one is pretty close to Audubon

Floral Court

Floral Court

This is the closest comparison to Audubon as the housing is mostly that foursquare style, and the people do maintain their lawns up to the central walkway (which in this case is a nice herringbone brick pattern) as individual lawns.

About mid-court there is this little fountain, and note the low iron fence behind it (vs. chain link).

About mid-court there is this little fountain, and note the low iron fence behind it (vs. chain link).

Fountain Court

Fountain Court

For a different approach here is short court with a central lawn and flanking walks. There is some subtle but effective urban design going on here. Note the raised curbs around the walks, and near zero lot line development of the houses. No front yard, but the facades really define this intimate space, further articulated by the curbing and slight grade changes, which subtly emphasizes the central lawn and the “private” (albeit minimal) fore-yards.

These are neither the worst nor best of Louisville courts, but they do show the possibilities of this urban form, which inexplicably did not retain popularity. The first Louisville court, Belgravia, was built in 1900, the last two, Eutropia and Arcadia (akin to California bungalow courts), in 1924.

These are neither the worst nor best of Louisville courts, but they do show the possibilities of this urban form, which inexplicably did not retain popularity. The first Louisville court, Belgravia, was built in 1900, the last two, Eutropia and Arcadia (akin to California bungalow courts), in 1924.

This concept, houses facing pedestrian streets or greenways, would surface again via the well-known Radburn plan of the late 1920s, but would never win widespread acceptance in America.

Anyway, sort of cool to see a court in Dayton, but sad to see the run-down condition

Basically the houses face each other over a lawn and walkway instead of a street. Parking would be in rear garages.

Apparently in the past there was some planning here, as a walkway connects the court with a park in the next block, visible in the distance. An illustration of the possibility of working pedestrian paths and walks into a neighborhood:

Apparently in the past there was some planning here, as a walkway connects the court with a park in the next block, visible in the distance. An illustration of the possibility of working pedestrian paths and walks into a neighborhood: Two contrasting approaches to front yards: chain link & no chain link

Two contrasting approaches to front yards: chain link & no chain link

Louisville Courts

Demonstrating what courts look like if the landscaping and houses are maintained, here are five of the 17 Louisville courts (there were 20 at one time).

Louisville might have the largest concentration in the US, though I hear Richmond, VA has a few. The Louisville examples are all considered “streets”, have city street signs, and are shown as such on maps. There are a variety of housing styles on Louisville courts: bungalows (big and small), foursquares, apartment buildings, Victorian, even a court of shotgun houses.

Two South End Courts.

These are in Louisville’s “South End” (roughly equivalent to Dayton’s Belmont), in the Southern Heights neighborhood. You’ll note that people are not chain-linking their front yards; the central court space is being treated as a continuous lawn. Maybe not exactly comparable to Audubon as the court space here is pretty wide.

Ouerbacher Court.

Ouerbacher Court. This is a “private” court as it is secured by a gate from the street (of the 17 this is the only private one). There is a second court opening into this one at mid block, so an example of a”system” of courts. Note again, lack of fencing in the front yards, with the court being treated as a communal open space. In dimension this one is pretty close to Audubon

Floral Court

Floral CourtThis is the closest comparison to Audubon as the housing is mostly that foursquare style, and the people do maintain their lawns up to the central walkway (which in this case is a nice herringbone brick pattern) as individual lawns.

About mid-court there is this little fountain, and note the low iron fence behind it (vs. chain link).

About mid-court there is this little fountain, and note the low iron fence behind it (vs. chain link). Fountain Court

Fountain CourtFor a different approach here is short court with a central lawn and flanking walks. There is some subtle but effective urban design going on here. Note the raised curbs around the walks, and near zero lot line development of the houses. No front yard, but the facades really define this intimate space, further articulated by the curbing and slight grade changes, which subtly emphasizes the central lawn and the “private” (albeit minimal) fore-yards.

These are neither the worst nor best of Louisville courts, but they do show the possibilities of this urban form, which inexplicably did not retain popularity. The first Louisville court, Belgravia, was built in 1900, the last two, Eutropia and Arcadia (akin to California bungalow courts), in 1924.

These are neither the worst nor best of Louisville courts, but they do show the possibilities of this urban form, which inexplicably did not retain popularity. The first Louisville court, Belgravia, was built in 1900, the last two, Eutropia and Arcadia (akin to California bungalow courts), in 1924. This concept, houses facing pedestrian streets or greenways, would surface again via the well-known Radburn plan of the late 1920s, but would never win widespread acceptance in America.

Anyway, sort of cool to see a court in Dayton, but sad to see the run-down condition

Friday, April 25, 2008

Dayton Urban Affairs blogging...Great In Dayton

There seems to be some very good additions to the urban affairs blog collection here in Dayton.

This brand new one, "It's Great 'n Dayton" is quite interesting as it has been reporting on a recent neighborhood leadership conference or seminar hosted by (I think) UD.

Issues addressed are housing stock, neighborhoods, economic development, and so forth. There is also some discussion about suburbia and sprawl.

Issues addressed are housing stock, neighborhoods, economic development, and so forth. There is also some discussion about suburbia and sprawl.

This brand new one, "It's Great 'n Dayton" is quite interesting as it has been reporting on a recent neighborhood leadership conference or seminar hosted by (I think) UD.

Issues addressed are housing stock, neighborhoods, economic development, and so forth. There is also some discussion about suburbia and sprawl.

Issues addressed are housing stock, neighborhoods, economic development, and so forth. There is also some discussion about suburbia and sprawl.

Carless in Dayton

Not having a car consigns one to economic isolation in a place like Dayton, where only 2% of commuters use public transit. But there are suprising concentrations of carlessness in the metro area.

The 2000 census provides a snapshot of the situation. The census measures the number of occupied housing units without access to a vehicle, which seems like an odd way to count carlessness. But one could use this as an indirect proxy by saying occupied housing unit = household (more or less). The census provides these numbers by tract.

Mapping Carlessness

So, counting up the tracts, coming up with a percentage, and then arranging them from lowest to highest, one can ascertain breaks and clusters of carlessness. The median is 6.3% carless units per tract, but there are some big concentrations, particulary downtown, where a whopping 70% of the units are carless, probably do to the concentration of senior housing downtown.

Then a collection of higher tracts, mostly close-in areas, then some lower breaks. After a plateau things go on a slow slide down to zero.

Mapping it out to the median value, one sees some concentrations, mostly in west and east Dayton, but also out in Drexel and up off of Dixie in Harrison Township, and one just south of Dorothy Lane in nothern Kettering. The little apartement cluster south of Town & Country also appears.

Mapping it out to the median value, one sees some concentrations, mostly in west and east Dayton, but also out in Drexel and up off of Dixie in Harrison Township, and one just south of Dorothy Lane in nothern Kettering. The little apartement cluster south of Town & Country also appears.

Taking a close up of the city, and noting the highest tracts. One can see that at least two are the sites of large public housing projects. Laying in the assumed route of the propose streetcar, one can see it doesn't go where the presumed market would be, aside from downtown. One would think a streetcar up West Third or along US 35 somehow would make more sense given the high % of carless housholds here.

Taking a close up of the city, and noting the highest tracts. One can see that at least two are the sites of large public housing projects. Laying in the assumed route of the propose streetcar, one can see it doesn't go where the presumed market would be, aside from downtown. One would think a streetcar up West Third or along US 35 somehow would make more sense given the high % of carless housholds here.

Transit Commuters

The census provides a projection based on a count of riders per tract, number of transit and non transit commuters (16 years or older who use public transit to get to work).

Its interesting that in this case the commuters don't necessarily overlap with high % of carlessness...in fact only the "West Old North Dayton " area (Parkside Homes) appears in the highest cohort for carless and transit commuting.

There are some pretty clear breaks here at around 100 riders per tract. I identify two clusters above the 100 rider break, and two below.

Then, mapping it out. In this case Oregon and South Park appear in the top rider tracts, but also the neighborhood around Lexington Avenue and neighorbhoods around Salem Avenue.

Then, mapping it out. In this case Oregon and South Park appear in the top rider tracts, but also the neighborhood around Lexington Avenue and neighorbhoods around Salem Avenue.

Due to the large population size some south suburban tracts show up as well, with a slight concentration of riders in the apartments between Alex and I-75 near the Dayton Mall.

Now, doing a quick and dirty correlation between high carless and high transit usage to come up with some tracts that rely on public transit. All are more ore less in the city

Now, doing a quick and dirty correlation between high carless and high transit usage to come up with some tracts that rely on public transit. All are more ore less in the city

Expanding the map, one sees Westwood,the neighborhoods between Salem and Main, Lexington Avenue, Lower Dayton View, Desot0-Bass & Parkside Homes areas, Inner East, South Park/Oregon, and, interestingly, the old "interurban era" plats on North Dixie in Harrison Township.

Expanding the map, one sees Westwood,the neighborhoods between Salem and Main, Lexington Avenue, Lower Dayton View, Desot0-Bass & Parkside Homes areas, Inner East, South Park/Oregon, and, interestingly, the old "interurban era" plats on North Dixie in Harrison Township.

Laying in the streetcar route, it again doesnt seem to help much except for downtown and maybe South Park.

Laying in the streetcar route, it again doesnt seem to help much except for downtown and maybe South Park.

Travel Time

The census also provides some interesting projectsion for travel times. It groups riders by whether they take public transit or "some other" form of commuting (which probably means car in Dayton's case, but could mean walking or bike), and then by how long it takes them to get to work (and from work), from 30 minutes or less up to 60 minutes or more.

So one can see some very interesting patterns here, mainly that it if time is valuable its best to not to rely on public transit. A whopping 70% of "non transit" commuters take 30 minutes or less to commute. Only 6.4% take more than 45 minutes.

How does this play out for transit users in areas of high transit commuting?

How does this play out for transit users in areas of high transit commuting?

Here are the groupings of tracts, with % of commuters by travel time shown as pie charts. In all cases it takes 35% or more of commuters a trip of 45 minutes or more to commute to work.

The aggregating of percentages masks some worst cases. In the case of that small tract near the Dayton Mall, 503.03, all the transit riders had a trip of 60 minutes or more to work.

The aggregating of percentages masks some worst cases. In the case of that small tract near the Dayton Mall, 503.03, all the transit riders had a trip of 60 minutes or more to work.

Due to the "edgeless city" dispersed suburban auto-centric development patterns of both manufacturing and service work public transit doesnt work well, requiring lots of transfers. Lack of frequency also adds to travel time as due to infrequent headways (plus a viscious cycle as people avoid transit due to inconvience, leading to more route and schedule cutbacks, leading to more transit avoidance).

One wonders if it would make more sense to scrap scheduled routes and default to an on-demand or ad-hoc jitney system.

The 2000 census provides a snapshot of the situation. The census measures the number of occupied housing units without access to a vehicle, which seems like an odd way to count carlessness. But one could use this as an indirect proxy by saying occupied housing unit = household (more or less). The census provides these numbers by tract.

Mapping Carlessness

So, counting up the tracts, coming up with a percentage, and then arranging them from lowest to highest, one can ascertain breaks and clusters of carlessness. The median is 6.3% carless units per tract, but there are some big concentrations, particulary downtown, where a whopping 70% of the units are carless, probably do to the concentration of senior housing downtown.

Then a collection of higher tracts, mostly close-in areas, then some lower breaks. After a plateau things go on a slow slide down to zero.

Mapping it out to the median value, one sees some concentrations, mostly in west and east Dayton, but also out in Drexel and up off of Dixie in Harrison Township, and one just south of Dorothy Lane in nothern Kettering. The little apartement cluster south of Town & Country also appears.

Mapping it out to the median value, one sees some concentrations, mostly in west and east Dayton, but also out in Drexel and up off of Dixie in Harrison Township, and one just south of Dorothy Lane in nothern Kettering. The little apartement cluster south of Town & Country also appears. Taking a close up of the city, and noting the highest tracts. One can see that at least two are the sites of large public housing projects. Laying in the assumed route of the propose streetcar, one can see it doesn't go where the presumed market would be, aside from downtown. One would think a streetcar up West Third or along US 35 somehow would make more sense given the high % of carless housholds here.

Taking a close up of the city, and noting the highest tracts. One can see that at least two are the sites of large public housing projects. Laying in the assumed route of the propose streetcar, one can see it doesn't go where the presumed market would be, aside from downtown. One would think a streetcar up West Third or along US 35 somehow would make more sense given the high % of carless housholds here.

Transit Commuters

The census provides a projection based on a count of riders per tract, number of transit and non transit commuters (16 years or older who use public transit to get to work).

Its interesting that in this case the commuters don't necessarily overlap with high % of carlessness...in fact only the "West Old North Dayton " area (Parkside Homes) appears in the highest cohort for carless and transit commuting.

There are some pretty clear breaks here at around 100 riders per tract. I identify two clusters above the 100 rider break, and two below.

Then, mapping it out. In this case Oregon and South Park appear in the top rider tracts, but also the neighborhood around Lexington Avenue and neighorbhoods around Salem Avenue.

Then, mapping it out. In this case Oregon and South Park appear in the top rider tracts, but also the neighborhood around Lexington Avenue and neighorbhoods around Salem Avenue.Due to the large population size some south suburban tracts show up as well, with a slight concentration of riders in the apartments between Alex and I-75 near the Dayton Mall.

Now, doing a quick and dirty correlation between high carless and high transit usage to come up with some tracts that rely on public transit. All are more ore less in the city

Now, doing a quick and dirty correlation between high carless and high transit usage to come up with some tracts that rely on public transit. All are more ore less in the city Expanding the map, one sees Westwood,the neighborhoods between Salem and Main, Lexington Avenue, Lower Dayton View, Desot0-Bass & Parkside Homes areas, Inner East, South Park/Oregon, and, interestingly, the old "interurban era" plats on North Dixie in Harrison Township.

Expanding the map, one sees Westwood,the neighborhoods between Salem and Main, Lexington Avenue, Lower Dayton View, Desot0-Bass & Parkside Homes areas, Inner East, South Park/Oregon, and, interestingly, the old "interurban era" plats on North Dixie in Harrison Township. Laying in the streetcar route, it again doesnt seem to help much except for downtown and maybe South Park.

Laying in the streetcar route, it again doesnt seem to help much except for downtown and maybe South Park.Travel Time

The census also provides some interesting projectsion for travel times. It groups riders by whether they take public transit or "some other" form of commuting (which probably means car in Dayton's case, but could mean walking or bike), and then by how long it takes them to get to work (and from work), from 30 minutes or less up to 60 minutes or more.

So one can see some very interesting patterns here, mainly that it if time is valuable its best to not to rely on public transit. A whopping 70% of "non transit" commuters take 30 minutes or less to commute. Only 6.4% take more than 45 minutes.

How does this play out for transit users in areas of high transit commuting?

How does this play out for transit users in areas of high transit commuting?Here are the groupings of tracts, with % of commuters by travel time shown as pie charts. In all cases it takes 35% or more of commuters a trip of 45 minutes or more to commute to work.

The aggregating of percentages masks some worst cases. In the case of that small tract near the Dayton Mall, 503.03, all the transit riders had a trip of 60 minutes or more to work.

The aggregating of percentages masks some worst cases. In the case of that small tract near the Dayton Mall, 503.03, all the transit riders had a trip of 60 minutes or more to work.Due to the "edgeless city" dispersed suburban auto-centric development patterns of both manufacturing and service work public transit doesnt work well, requiring lots of transfers. Lack of frequency also adds to travel time as due to infrequent headways (plus a viscious cycle as people avoid transit due to inconvience, leading to more route and schedule cutbacks, leading to more transit avoidance).

One wonders if it would make more sense to scrap scheduled routes and default to an on-demand or ad-hoc jitney system.

Sunday, April 20, 2008

Daytonology Blog Changes

New to the Blogroll

Dayton Politics Blog. Good old fashioned political blogging…lots of muckraking and roasting, probably GOP, but maybe just-anti incumbent. One can appreciated the sour, acerbic style as a true voice of the genus loci.

Dayton Most Metro Forum: The premier online place in Dayton for non-political urban affairs discussion, with a forum getting substantial contributions by folks active in the arts/gentrification/urban living/creative class scene.

Posting Schedule:

New blog posts will be made on Friday and Saturday nights (usually later), and Sunday mornings. Surf in here on Sunday night and one will find new content, if there is any.

Blog Comments

Commenting is closed. If anyone feels a need to comment go to DaytonOS. Everything on this blog is reposted at DaytonOS (linked at blogroll), and they have a comments feature (here is a screen shot on how to find it, "Dayton Blog Feeds").

Blog Content

Lengthy, image-intensive historical/geographical “analyses” posts are being dropped. These will be posted at Urban Ohio (linked at the blogroll). Posts on local the music scene are also being dropped as this are covered better elsewhere, particularly at the “Dayton Shows” and “Bhudda Den” (links over at the blogroll).

Dayton Politics Blog. Good old fashioned political blogging…lots of muckraking and roasting, probably GOP, but maybe just-anti incumbent. One can appreciated the sour, acerbic style as a true voice of the genus loci.

Dayton Most Metro Forum: The premier online place in Dayton for non-political urban affairs discussion, with a forum getting substantial contributions by folks active in the arts/gentrification/urban living/creative class scene.

Posting Schedule:

New blog posts will be made on Friday and Saturday nights (usually later), and Sunday mornings. Surf in here on Sunday night and one will find new content, if there is any.

Blog Comments

Commenting is closed. If anyone feels a need to comment go to DaytonOS. Everything on this blog is reposted at DaytonOS (linked at blogroll), and they have a comments feature (here is a screen shot on how to find it, "Dayton Blog Feeds").

Blog Content

Lengthy, image-intensive historical/geographical “analyses” posts are being dropped. These will be posted at Urban Ohio (linked at the blogroll). Posts on local the music scene are also being dropped as this are covered better elsewhere, particularly at the “Dayton Shows” and “Bhudda Den” (links over at the blogroll).

Saturday, April 19, 2008

Designs on the Arcade Block.

Its time to get real about the Arcade. There is zero interest in saving this building aside from the FSA activists, who don’t have the money to make it happen. The most likely redeveloper said he needs some gap financing just to renovate the flanking buildings (don’t ask about the rotunda), which won’t be coming from local government.

Adaptive re-use is not feasible. Not in Dayton. So tear it down.

And what next?

How about nothing. No building at all. There is already a surfeit of vacant space downtown, so why build more vacant space?

Instead how about an Arcade Park. Here is a proposal for one. Replace a building with a landscape that “remembers” the building.

The concept is to use the building lines as the source for a landscape plan, with forested areas on the site of the three flanking buildings, and a water feature where the rotunda used to be.

The concept is to use the building lines as the source for a landscape plan, with forested areas on the site of the three flanking buildings, and a water feature where the rotunda used to be.

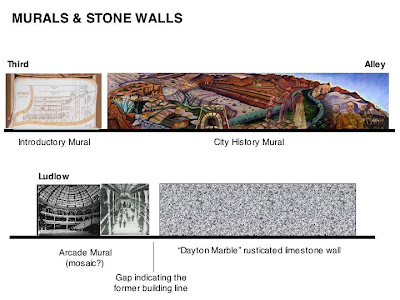

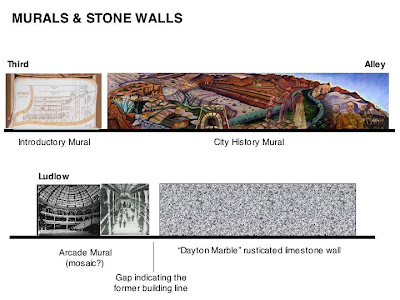

The scheme would also to use fragments of the arcade, including the 3rd Street façade, relocated as a “rear” for the McCrorys building, and walls and murals to activate the space a bit, and as visual barriers from the mid block alley. Sight-lines and axis could be developed to focus on surrounding buildings.

Pretzinger Lane would be extended north through the block to 3rd Street.

And this scheme would also tear down the vacant Lindsey Building and the vacant building to the west of the Arcade.

Arcade fragment would be a part of the colonnade from the arcade, the 3rd Street Façade, the tin turkeys (moved to ground level pedestals around a water feature, and door surrounds from the flanking buildings as “gateways” to the site.

Arcade fragment would be a part of the colonnade from the arcade, the 3rd Street Façade, the tin turkeys (moved to ground level pedestals around a water feature, and door surrounds from the flanking buildings as “gateways” to the site.

Vertical elements would be a framework to support the colonnade and clock tower (similar to the RTA one on Main) and kiosk at the 3rd street entrance, walls as a barrier for the alley, murals, and a mix of walls and fences around the forest areas

Vertical elements would be a framework to support the colonnade and clock tower (similar to the RTA one on Main) and kiosk at the 3rd street entrance, walls as a barrier for the alley, murals, and a mix of walls and fences around the forest areas

Walls and murals would look like this, maybe. Limestone wall would be rough, to provide some visual interest and be less attractive for graffiti .

Walls and murals would look like this, maybe. Limestone wall would be rough, to provide some visual interest and be less attractive for graffiti .

Tree planting. Trees could be nice features along the walkways as well as forest elements, with masses and absences setting up little forecourt and open spaces near murals and in front of buildings

Tree planting. Trees could be nice features along the walkways as well as forest elements, with masses and absences setting up little forecourt and open spaces near murals and in front of buildings

Pavement surfaces would differ depending on the nature of the space, with a mix of decorative brick and concrete. Natural surfaces would be water, a small lawn area, and a “forest floor”, with bark or just leaves and underbrush. The water feature could be grass, too, or maybe a plaza.

Pavement surfaces would differ depending on the nature of the space, with a mix of decorative brick and concrete. Natural surfaces would be water, a small lawn area, and a “forest floor”, with bark or just leaves and underbrush. The water feature could be grass, too, or maybe a plaza.

The Arcade Park could be the start of an open space system, with perhaps a mall and park in the location of the DDN plant and news offices (the old “Cox” era building would be saved as a shell or classical ruin), landscaping on Pretizinger Lane, etc.

The Arcade Park could be the start of an open space system, with perhaps a mall and park in the location of the DDN plant and news offices (the old “Cox” era building would be saved as a shell or classical ruin), landscaping on Pretizinger Lane, etc.

To do something like this for the Arcade might cost as much as restoring it, but maybe a minimal approach, just using grass and trees and some sidewalks, extending Pretzinger, and saving/relocating the 3rd Street Façade would be a realistic solution for the site after demolition.

To do something like this for the Arcade might cost as much as restoring it, but maybe a minimal approach, just using grass and trees and some sidewalks, extending Pretzinger, and saving/relocating the 3rd Street Façade would be a realistic solution for the site after demolition.

Adaptive re-use is not feasible. Not in Dayton. So tear it down.

And what next?

How about nothing. No building at all. There is already a surfeit of vacant space downtown, so why build more vacant space?

Instead how about an Arcade Park. Here is a proposal for one. Replace a building with a landscape that “remembers” the building.

The concept is to use the building lines as the source for a landscape plan, with forested areas on the site of the three flanking buildings, and a water feature where the rotunda used to be.

The concept is to use the building lines as the source for a landscape plan, with forested areas on the site of the three flanking buildings, and a water feature where the rotunda used to be.The scheme would also to use fragments of the arcade, including the 3rd Street façade, relocated as a “rear” for the McCrorys building, and walls and murals to activate the space a bit, and as visual barriers from the mid block alley. Sight-lines and axis could be developed to focus on surrounding buildings.

Pretzinger Lane would be extended north through the block to 3rd Street.

And this scheme would also tear down the vacant Lindsey Building and the vacant building to the west of the Arcade.

Arcade fragment would be a part of the colonnade from the arcade, the 3rd Street Façade, the tin turkeys (moved to ground level pedestals around a water feature, and door surrounds from the flanking buildings as “gateways” to the site.

Arcade fragment would be a part of the colonnade from the arcade, the 3rd Street Façade, the tin turkeys (moved to ground level pedestals around a water feature, and door surrounds from the flanking buildings as “gateways” to the site. Vertical elements would be a framework to support the colonnade and clock tower (similar to the RTA one on Main) and kiosk at the 3rd street entrance, walls as a barrier for the alley, murals, and a mix of walls and fences around the forest areas

Vertical elements would be a framework to support the colonnade and clock tower (similar to the RTA one on Main) and kiosk at the 3rd street entrance, walls as a barrier for the alley, murals, and a mix of walls and fences around the forest areas Walls and murals would look like this, maybe. Limestone wall would be rough, to provide some visual interest and be less attractive for graffiti .

Walls and murals would look like this, maybe. Limestone wall would be rough, to provide some visual interest and be less attractive for graffiti .

Tree planting. Trees could be nice features along the walkways as well as forest elements, with masses and absences setting up little forecourt and open spaces near murals and in front of buildings

Tree planting. Trees could be nice features along the walkways as well as forest elements, with masses and absences setting up little forecourt and open spaces near murals and in front of buildings Pavement surfaces would differ depending on the nature of the space, with a mix of decorative brick and concrete. Natural surfaces would be water, a small lawn area, and a “forest floor”, with bark or just leaves and underbrush. The water feature could be grass, too, or maybe a plaza.

Pavement surfaces would differ depending on the nature of the space, with a mix of decorative brick and concrete. Natural surfaces would be water, a small lawn area, and a “forest floor”, with bark or just leaves and underbrush. The water feature could be grass, too, or maybe a plaza.  The Arcade Park could be the start of an open space system, with perhaps a mall and park in the location of the DDN plant and news offices (the old “Cox” era building would be saved as a shell or classical ruin), landscaping on Pretizinger Lane, etc.

The Arcade Park could be the start of an open space system, with perhaps a mall and park in the location of the DDN plant and news offices (the old “Cox” era building would be saved as a shell or classical ruin), landscaping on Pretizinger Lane, etc.  To do something like this for the Arcade might cost as much as restoring it, but maybe a minimal approach, just using grass and trees and some sidewalks, extending Pretzinger, and saving/relocating the 3rd Street Façade would be a realistic solution for the site after demolition.

To do something like this for the Arcade might cost as much as restoring it, but maybe a minimal approach, just using grass and trees and some sidewalks, extending Pretzinger, and saving/relocating the 3rd Street Façade would be a realistic solution for the site after demolition.

Repositioning Dayton

One of this articles on the citys new downtown revitalization fund had an interesting lead:

"The city of Dayton wants to reposition its downtown core and the ring of surrounding neighborhoods to be more competitive when it comes to creating jobs, housing and amenities."

This is a larger policy intent than just adaptive reuse of Main Street property. Note the reference to "ring of surrounding neighborhoods". What does that mean?

Here is a map from the city planning department showing historic districts. I drew in some other things going on, like UD, MVH, whatever MVH is doing along Warren Street, the streetcar, Webster Station, Tech Town, and so forth. This is the area were theres' been a lot of announced projects, where there's bveen a lot of action.

Then I drew a line around whats close enough in as sort of a "Greater Downtown", whats walkable from downtown and across downtown. This could be the close in neighborhoods the article is talking about:

But that leaves out a lot. Expanding the concept to bring in some of the outlying historic districts, Wright-Dunbar, and the UD/Brown Street corridor:

But that leaves out a lot. Expanding the concept to bring in some of the outlying historic districts, Wright-Dunbar, and the UD/Brown Street corridor:

This could be the new area of emphasis, the "Dayton" the city wants to market or position itself as an collection of "vintage neighborhoods" and redevelopment sites as its new area of focus?

This could be the new area of emphasis, the "Dayton" the city wants to market or position itself as an collection of "vintage neighborhoods" and redevelopment sites as its new area of focus?

But this does seem a bit like urban triage. Taking a broader look, here is the rest of the city, using that board-up/vacancy map, showing these concentrations as potential "zones of destruction" that the city is going to slowly demolish (and perhaps rebuild?).

One can see there is overlap with the historic districts, which means maybe some of these places aren't really viable as historic districts (Dayton View, for one, maybe Huffman), or need a lot more interest than they are getting.

So one can see the area shaded in red as place the city (and other players like UD and MVH, via its quiet slum clearance program) might be focusing on, while writing off the "zones of destruction". The rest of the city is probably OK, not failing and not recieving the "repositioning" as was mentioned in the byline.

Interesting to observe how this "zona rosa" sort of dips down toward Oakwood via UD/Brown Street, as maybe seeing this "repositioned Dayton" as a hipster/gentrifier/creative class extension of Oakwood?

"The city of Dayton wants to reposition its downtown core and the ring of surrounding neighborhoods to be more competitive when it comes to creating jobs, housing and amenities."

This is a larger policy intent than just adaptive reuse of Main Street property. Note the reference to "ring of surrounding neighborhoods". What does that mean?

Here is a map from the city planning department showing historic districts. I drew in some other things going on, like UD, MVH, whatever MVH is doing along Warren Street, the streetcar, Webster Station, Tech Town, and so forth. This is the area were theres' been a lot of announced projects, where there's bveen a lot of action.

Then I drew a line around whats close enough in as sort of a "Greater Downtown", whats walkable from downtown and across downtown. This could be the close in neighborhoods the article is talking about:

But that leaves out a lot. Expanding the concept to bring in some of the outlying historic districts, Wright-Dunbar, and the UD/Brown Street corridor:

But that leaves out a lot. Expanding the concept to bring in some of the outlying historic districts, Wright-Dunbar, and the UD/Brown Street corridor: This could be the new area of emphasis, the "Dayton" the city wants to market or position itself as an collection of "vintage neighborhoods" and redevelopment sites as its new area of focus?

This could be the new area of emphasis, the "Dayton" the city wants to market or position itself as an collection of "vintage neighborhoods" and redevelopment sites as its new area of focus?But this does seem a bit like urban triage. Taking a broader look, here is the rest of the city, using that board-up/vacancy map, showing these concentrations as potential "zones of destruction" that the city is going to slowly demolish (and perhaps rebuild?).

One can see there is overlap with the historic districts, which means maybe some of these places aren't really viable as historic districts (Dayton View, for one, maybe Huffman), or need a lot more interest than they are getting.

So one can see the area shaded in red as place the city (and other players like UD and MVH, via its quiet slum clearance program) might be focusing on, while writing off the "zones of destruction". The rest of the city is probably OK, not failing and not recieving the "repositioning" as was mentioned in the byline.

Interesting to observe how this "zona rosa" sort of dips down toward Oakwood via UD/Brown Street, as maybe seeing this "repositioned Dayton" as a hipster/gentrifier/creative class extension of Oakwood?

Friday, April 18, 2008

Downtown Revitalization Plan: Looks good on paper, but...

...maybe too narrow-focused?

You've probably seen this front page story in this Fridays' DDN, about how the city wants a plan to incentivize "vintage structures".

The paper says the there will be $1M a year for five years to:

"...promote transformation of vintage downtown Main Street buildings with financial incentives for developers who take them on as projects..."

..and goes on to say that target uses are jobs and housing.

Note that this is just for "vintage downtown Main Street buildings". Presumably vintage means prior to WWII.

Which begs the question on how many of these are left, considering Main Street has lost a lot of prewar structures via various urban renewal schemes and new construction. Arguably Main Street has the lowest concentration of prewar buildings.

Mapping out vintage Main Street buildings, and color coding them by private and public/non-proift use, one see there are 10 in private hands, and two (Kuhns and McCrory) have recently been renovated (maybe the McCrorys could use a bit more).

Note that most of these buildings are over 7 stories tall, actually most of the them are small high- or mid-rises. Probably somewhat costly to renovate. One, the Lindsey Building, is owned by the city, but is vacant. Presumably the city might be interested giving it to a developer to renovate.

Note that most of these buildings are over 7 stories tall, actually most of the them are small high- or mid-rises. Probably somewhat costly to renovate. One, the Lindsey Building, is owned by the city, but is vacant. Presumably the city might be interested giving it to a developer to renovate.

But what is noticeable are the very few older propertys and the relatively large scale of the buildings.

Vintage Downtown Beyond Main

Broadening the look, diagramming the core of downtown by including blocks flanking Ludlow and Jefferson Streets, one sees considerably more vintage buildings, at smaller scale.

..which also occur in loose clusters. Two of these have sort of historic district designation, either nominated or eligible...Terra Cotta (maybe), and Fire Blocks and vicinty.

..which also occur in loose clusters. Two of these have sort of historic district designation, either nominated or eligible...Terra Cotta (maybe), and Fire Blocks and vicinty.

Another sort of cuts across the heart of downtown, including Ludlow, the Arcade, and Main south of 3rd. The last undisturbed prewar block front (no parking lots or new construction) is in this cluster..north side of 4th, between Ludlow and Main.

The Fire Blocks cluster on 3rd between Jefferson and St Clair has the last mostly intact prewar streetscape, with minimal disturbance by new construction and parking lots (though these are on the street they are not large enought to distort the streetscape)

What Will $1M per year Buy?

Given the scale of the buildings on Main, not much. Example from Louisville compared to Dayton:

An old hotel of roughly the same scale as a Dayton midrise (but more elaborate inside) cost $20M to renovate into mixed use (but mostly residential).

Comparing it to the Fidelity Building, perhaps $10M to adpatively re-use the Fidelity? $1M wont go too far there (10% of reno cost)?

Perhaps a much larger deal fund would be needed to do the kind of large-scale renovations that would be needed on Main for places like Center City, Fidelity, the Lindsey Building.

Perhaps a much larger deal fund would be needed to do the kind of large-scale renovations that would be needed on Main for places like Center City, Fidelity, the Lindsey Building.

$1M a year might go much farther if used for the smaller vintage building clusters off Main. Buildings like this, where the issues are in part code compliance, restoration to NPS standard, fire safety, hazmat abatement, where a city grant could help to reduce development costs.

Since these occur in clusters there could be a concerted effort to regenerate these two ways:

Since these occur in clusters there could be a concerted effort to regenerate these two ways:

Note that this isn't to denigrate large scale renovations of downtown office buildings. This could be done as well, but needs a more robust funding stream. $1M/year is not going to help too much. The impact would be greater if this money was focused in the older building clusters off Main.

You've probably seen this front page story in this Fridays' DDN, about how the city wants a plan to incentivize "vintage structures".

The paper says the there will be $1M a year for five years to:

"...promote transformation of vintage downtown Main Street buildings with financial incentives for developers who take them on as projects..."

..and goes on to say that target uses are jobs and housing.

Note that this is just for "vintage downtown Main Street buildings". Presumably vintage means prior to WWII.

Which begs the question on how many of these are left, considering Main Street has lost a lot of prewar structures via various urban renewal schemes and new construction. Arguably Main Street has the lowest concentration of prewar buildings.

Mapping out vintage Main Street buildings, and color coding them by private and public/non-proift use, one see there are 10 in private hands, and two (Kuhns and McCrory) have recently been renovated (maybe the McCrorys could use a bit more).

Note that most of these buildings are over 7 stories tall, actually most of the them are small high- or mid-rises. Probably somewhat costly to renovate. One, the Lindsey Building, is owned by the city, but is vacant. Presumably the city might be interested giving it to a developer to renovate.

Note that most of these buildings are over 7 stories tall, actually most of the them are small high- or mid-rises. Probably somewhat costly to renovate. One, the Lindsey Building, is owned by the city, but is vacant. Presumably the city might be interested giving it to a developer to renovate. But what is noticeable are the very few older propertys and the relatively large scale of the buildings.

Vintage Downtown Beyond Main

Broadening the look, diagramming the core of downtown by including blocks flanking Ludlow and Jefferson Streets, one sees considerably more vintage buildings, at smaller scale.

..which also occur in loose clusters. Two of these have sort of historic district designation, either nominated or eligible...Terra Cotta (maybe), and Fire Blocks and vicinty.

..which also occur in loose clusters. Two of these have sort of historic district designation, either nominated or eligible...Terra Cotta (maybe), and Fire Blocks and vicinty. Another sort of cuts across the heart of downtown, including Ludlow, the Arcade, and Main south of 3rd. The last undisturbed prewar block front (no parking lots or new construction) is in this cluster..north side of 4th, between Ludlow and Main.

The Fire Blocks cluster on 3rd between Jefferson and St Clair has the last mostly intact prewar streetscape, with minimal disturbance by new construction and parking lots (though these are on the street they are not large enought to distort the streetscape)

What Will $1M per year Buy?

Given the scale of the buildings on Main, not much. Example from Louisville compared to Dayton:

An old hotel of roughly the same scale as a Dayton midrise (but more elaborate inside) cost $20M to renovate into mixed use (but mostly residential).

Comparing it to the Fidelity Building, perhaps $10M to adpatively re-use the Fidelity? $1M wont go too far there (10% of reno cost)?

Perhaps a much larger deal fund would be needed to do the kind of large-scale renovations that would be needed on Main for places like Center City, Fidelity, the Lindsey Building.

Perhaps a much larger deal fund would be needed to do the kind of large-scale renovations that would be needed on Main for places like Center City, Fidelity, the Lindsey Building.$1M a year might go much farther if used for the smaller vintage building clusters off Main. Buildings like this, where the issues are in part code compliance, restoration to NPS standard, fire safety, hazmat abatement, where a city grant could help to reduce development costs.

Since these occur in clusters there could be a concerted effort to regenerate these two ways:

Since these occur in clusters there could be a concerted effort to regenerate these two ways:- Residential districts, using the $1M/yr fund to work on converting upper floors to residential, perhaps to fund fire code compliance work

- Ground floor use, using the $M/yr fund to assist in ground floor tenant improvements for new and existing businesses (retail, nightclubs, food & drink, gallerys, etc).

Note that this isn't to denigrate large scale renovations of downtown office buildings. This could be done as well, but needs a more robust funding stream. $1M/year is not going to help too much. The impact would be greater if this money was focused in the older building clusters off Main.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Power Blocks II: Ohmer's Factory & Ice Avenue

More examples of the mid-block industrial loft typology:

Ohmer’s Factory

Another example of loft construction in the heart of the city is the Ohmer Furniture factory. Built sometime after 1875 facing 1st Street, and was replaced in the 1920s by one of those parking garages that look like commercial buildings (but with a nice terra cotta facade)

(stage fly of the Victoria is immediatly to the right in the pix)

(stage fly of the Victoria is immediatly to the right in the pix)

A second loft building was built to the rear, connected to the main factory by a bridge. It isn’t a true power block as it was not built on spec, but for a single business. The concept of high density mid-block infill is still evident, though, which makes it of the type.

One can see the building in the background of this Main Street pix (old wood building with the long porch was antebellum, and a tavern or saloon of some sort). Ohmers original showroom of 1875 (perhaps a workshop too, on the upper floors) was next door.

One can see the building in the background of this Main Street pix (old wood building with the long porch was antebellum, and a tavern or saloon of some sort). Ohmers original showroom of 1875 (perhaps a workshop too, on the upper floors) was next door.

Ice Avenue Lofts

Ice Avenue Lofts

Only one of these 19th century downtown power blocks still stands, converted into lofts. It's also a good example of how secondary streets and alleys developed downtown to provide better access into the blocks.

A tannery appears on the site in the 1875 combination atlas and in the 1889 Sanborn, but based on the building heights, 2, 1, and 4 stories, this isn’t the building we see today, except, maybe, for the side facing Ice Street, which may have been part of this original tannery.

A tannery appears on the site in the 1875 combination atlas and in the 1889 Sanborn, but based on the building heights, 2, 1, and 4 stories, this isn’t the building we see today, except, maybe, for the side facing Ice Street, which may have been part of this original tannery.

One can see a new alley running north/south between Spratt (Ice) and 1st.

One can see a new alley running north/south between Spratt (Ice) and 1st.

And a modern photo, houses along St Clair have been replaced by a commercial buildings, but this is probably how these power blocks looked, setting back away from the main streets.

By the 1898 Sanborn (north is to the left) one can see a true loft use, with multiple companies occupying the building. The side alley is still there, too. This was a pretty dense little block.

By the 1898 Sanborn (north is to the left) one can see a true loft use, with multiple companies occupying the building. The side alley is still there, too. This was a pretty dense little block.

(also, the ice works can be seen at the intersecton of Harris and Spratt)

(also, the ice works can be seen at the intersecton of Harris and Spratt)

The building today, pretty sure this is the last surviving 19th century industrial building in the heart of downtown (i.e. on the the original plat).

Ohmer’s Factory

Another example of loft construction in the heart of the city is the Ohmer Furniture factory. Built sometime after 1875 facing 1st Street, and was replaced in the 1920s by one of those parking garages that look like commercial buildings (but with a nice terra cotta facade)

(stage fly of the Victoria is immediatly to the right in the pix)

(stage fly of the Victoria is immediatly to the right in the pix)A second loft building was built to the rear, connected to the main factory by a bridge. It isn’t a true power block as it was not built on spec, but for a single business. The concept of high density mid-block infill is still evident, though, which makes it of the type.

One can see the building in the background of this Main Street pix (old wood building with the long porch was antebellum, and a tavern or saloon of some sort). Ohmers original showroom of 1875 (perhaps a workshop too, on the upper floors) was next door.

One can see the building in the background of this Main Street pix (old wood building with the long porch was antebellum, and a tavern or saloon of some sort). Ohmers original showroom of 1875 (perhaps a workshop too, on the upper floors) was next door. Ice Avenue Lofts

Ice Avenue LoftsOnly one of these 19th century downtown power blocks still stands, converted into lofts. It's also a good example of how secondary streets and alleys developed downtown to provide better access into the blocks.

A tannery appears on the site in the 1875 combination atlas and in the 1889 Sanborn, but based on the building heights, 2, 1, and 4 stories, this isn’t the building we see today, except, maybe, for the side facing Ice Street, which may have been part of this original tannery.

A tannery appears on the site in the 1875 combination atlas and in the 1889 Sanborn, but based on the building heights, 2, 1, and 4 stories, this isn’t the building we see today, except, maybe, for the side facing Ice Street, which may have been part of this original tannery. One can see a new alley running north/south between Spratt (Ice) and 1st.

One can see a new alley running north/south between Spratt (Ice) and 1st.And a modern photo, houses along St Clair have been replaced by a commercial buildings, but this is probably how these power blocks looked, setting back away from the main streets.

By the 1898 Sanborn (north is to the left) one can see a true loft use, with multiple companies occupying the building. The side alley is still there, too. This was a pretty dense little block.

By the 1898 Sanborn (north is to the left) one can see a true loft use, with multiple companies occupying the building. The side alley is still there, too. This was a pretty dense little block. (also, the ice works can be seen at the intersecton of Harris and Spratt)

(also, the ice works can be seen at the intersecton of Harris and Spratt)The building today, pretty sure this is the last surviving 19th century industrial building in the heart of downtown (i.e. on the the original plat).

Monday, April 14, 2008

Downtown Power Blocks I : Callahan Block

Daytonians used to have a different name for industrial lofts. Here they were called “power blocks” or “power buildings” instead of lofts. This was because these structures had their own power source, either a steam engine and belt & pulley transmission, or generator providing electric power.

As in examples in other cities power blocks were either built on spec, as sort of a vertical industrial park, or purpose-built for one company.

One of the older on-spec ones in Dayton, it seems, was the Callahan Power Building.

Apparently this structure dated from either the late 1870s or early 1880s. It was an example of a local industrialists venturing into commercial real-estate, which was a common phenomenon in 19th century Dayton. Callahan was an early foundry and machine shop, located on east 3rd (some of it is still there).

The proprietor (or his son) built commercial structures on Main, just north of Third. One was Dayton's first skyscraper.

The power building was built mid-block. The mark-up on this pic shows the expansion of National Cash Register in the building, eventually even expanding across the alley to an adjacent building, before Patterson built his own factory south of town.

The mark-up on this pic shows the expansion of National Cash Register in the building, eventually even expanding across the alley to an adjacent building, before Patterson built his own factory south of town.

As one sees from this earlier post, Delco did the same thing30 years later, but in a different “power building”.

Close inspection of Sanborn maps show the location of the chimney, boilers, engine, and freight elevator (near the large double doors for winching stuff up into the loft space), and a perhaps row of skylights running down the center of the factory. Two different views, one with up being east (1880s) the other with up being north (1890s) One can locate this building by cross referencing features visible in this pick with a Sanborn map

One can locate this building by cross referencing features visible in this pick with a Sanborn map  1. Water tower

1. Water tower

2. Bridge across alley

3. Roof hatch

4. Skylight

5. Chamfered corner of building. This puts the building on the block just east of Main, between 2nd and 3rd

This puts the building on the block just east of Main, between 2nd and 3rd  …and an aerial of the same block with the power block circled (sometime in the 1920s) showing the dense building fabric:

…and an aerial of the same block with the power block circled (sometime in the 1920s) showing the dense building fabric:

What’s fascinating is how the block is filled-in, and the system of back alleys, which are named and called “lanes”. The original city plat had east-west lanes but made no provision for north-south alleys paralleling Main Street. These and additional north-south lanes were added in various downtown blocks.

What’s fascinating is how the block is filled-in, and the system of back alleys, which are named and called “lanes”. The original city plat had east-west lanes but made no provision for north-south alleys paralleling Main Street. These and additional north-south lanes were added in various downtown blocks.

Deep lots permitted the development of a secondary urban fabric of storage, industrial, and service buildings. Lots eventually filled as street frontage buildings incrementally expanded to the rear, eventually joining up with the back lot buildings.

One sees this throughout downtown; the interior of certain downtown blocks was a veritable Kasbah of back lot structures of various heights, little yards and courts, narrow alleys and lanes, bridges between buildings over the alleys, and so forth.

As in examples in other cities power blocks were either built on spec, as sort of a vertical industrial park, or purpose-built for one company.

One of the older on-spec ones in Dayton, it seems, was the Callahan Power Building.

Apparently this structure dated from either the late 1870s or early 1880s. It was an example of a local industrialists venturing into commercial real-estate, which was a common phenomenon in 19th century Dayton. Callahan was an early foundry and machine shop, located on east 3rd (some of it is still there).

The proprietor (or his son) built commercial structures on Main, just north of Third. One was Dayton's first skyscraper.

The power building was built mid-block.

The mark-up on this pic shows the expansion of National Cash Register in the building, eventually even expanding across the alley to an adjacent building, before Patterson built his own factory south of town.

The mark-up on this pic shows the expansion of National Cash Register in the building, eventually even expanding across the alley to an adjacent building, before Patterson built his own factory south of town. As one sees from this earlier post, Delco did the same thing30 years later, but in a different “power building”.

Close inspection of Sanborn maps show the location of the chimney, boilers, engine, and freight elevator (near the large double doors for winching stuff up into the loft space), and a perhaps row of skylights running down the center of the factory. Two different views, one with up being east (1880s) the other with up being north (1890s)

One can locate this building by cross referencing features visible in this pick with a Sanborn map

One can locate this building by cross referencing features visible in this pick with a Sanborn map  1. Water tower

1. Water tower 2. Bridge across alley

3. Roof hatch

4. Skylight

5. Chamfered corner of building.

This puts the building on the block just east of Main, between 2nd and 3rd

This puts the building on the block just east of Main, between 2nd and 3rd  …and an aerial of the same block with the power block circled (sometime in the 1920s) showing the dense building fabric:

…and an aerial of the same block with the power block circled (sometime in the 1920s) showing the dense building fabric:  What’s fascinating is how the block is filled-in, and the system of back alleys, which are named and called “lanes”. The original city plat had east-west lanes but made no provision for north-south alleys paralleling Main Street. These and additional north-south lanes were added in various downtown blocks.

What’s fascinating is how the block is filled-in, and the system of back alleys, which are named and called “lanes”. The original city plat had east-west lanes but made no provision for north-south alleys paralleling Main Street. These and additional north-south lanes were added in various downtown blocks. Deep lots permitted the development of a secondary urban fabric of storage, industrial, and service buildings. Lots eventually filled as street frontage buildings incrementally expanded to the rear, eventually joining up with the back lot buildings.

One sees this throughout downtown; the interior of certain downtown blocks was a veritable Kasbah of back lot structures of various heights, little yards and courts, narrow alleys and lanes, bridges between buildings over the alleys, and so forth.