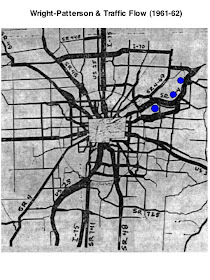

The I-675 story flagged the significance of Wright-Patterson AFB in driving development decisions. The next set of threads will take a closer look at the base and how it drove infrastructure planning, as a prelude to a closer look at Fairborn and Riverside.

The oldest part of the base came into being around the same time as the Conservancy Districts’ Huffman Dam retention basin, so the Conservancy drove early road and transportation re-routes as much as the base. The first re-routes were of Springfield Pike east of Riverside village. The actual route of the relocated Springfield Pike is unclear, but it did bypass Huffman Dam and pass under the re-routed Big Four and Erie Railroads.

A bridge across the railroads for Kaufman Avenue and a road atop Huffman Dam was also built at this time, with the dam road being the 3rd crossing of the Mad River bottoms out from Dayton.

Also shown is the Wright Brothers Monument and park, which came into being in the 1930s, as a draw for visitors from the city.

Later reroutes came during WWII base expansion, with the closure of Yellow Springs Road out from Riverside.

This aerial photo from a news clipping shows the 1933 adjustment of Springfield Pike through Riverside village, being the start of the destruction of this area by highway construction. In the distance one can see Huffman Dam and the early 1920s re-route of Springfield Pike around the dam.

The relatively new Wright Field cantonment area can be seen in the distance. This was the relocated McCook Field, and was probably drawing “reverse commuters” out from Dayton who used to work at McCook.

A ground level pix of the relocation of Springfield Street. One of the rows of telephone poles in the distance is for the interurban railroad, which provided passenger train service through the area.

During the ‘teens & ‘twenties Dayton grew eastward, up and over Tait's Point and Huffman Hill. The Third Street streetcar line ended at the same location as the todays trolleybus loop, but Third Street itself was extended over the hill to Yellow Springs Road, opposite the Wright Field airfield, with stub-outs for future streets. The Springfield Street realignments are also shown.

One can see some early subdivision activity in this area, east of Smithville Road, probably driven by 1920s speculative boom. The Depression intervened and most of these plats wouldn’t be built-out on till WWII and the postwar era.

World War II really made the base as a major employer for Dayton. Base expansion drove road relocations and improvements.

The expansion of the Wright Field airfield forced the relocation of the Third Street Extension, which was routed eastward to an endpoint opposite a new wartime housing and military supply area midway between Fairborn and Wright Field. On the western end (shown in this pix) was war worker housing in Overlook Mutual Homes.

The Third Street Extension, which would later be renamed Airway Drive and Colonel Glenn Highway, also provide a second access to Wright Field, relieving the traffic a bit on Springfield Pike.

Springfield Pike was drastically reconstructed as a quasi-expressway from Huffman Dam to Fairborn, with limited access since it passed through the base. This four lane divided highway is actually somewhat historic as itwas one of the first two such roads in Dayton (the other was US 25 north), and would have been Daytonians’ first experience with expressway driving (but without interchanges).

This new “Route 4 Expressway” helped with reverse commuting from Dayton to the Patterson Field part of the base.

WWII development east of Dayton can be seen as an early form of suburbanization, as the government constructed a mix of barracks and civilians and military housing between Wright & Patterson Fields and in Fariborn.

There was a lot of private sector development of various types, too, including the mostly jerry-built Wright View area. One can see how the Third Street Extension and the Route 4 Expressway served this busy area. One should note, too, the role of the Huffman Dam road, which connected the war worker housing areas and trailer parks on Valley Street to the base.

Wartime planning for the base was seeing a big expansion due to the somewhat cramped Wright Field, which would have made Burkhardt Avenue/Kemp Road a relocated Airway Drive. The planning also included a beltway to serve the various wartime housing projects and private sector development east of the city, connecting it to roads into and around the base and to the US highway system at the US 25 traffic circle in Northridge.

Though not shown here, this early planning for both bases was already envisioning true limited access for Route 4 and Airway Road, with early cloverleaf and half-cloverleaf interchange designs. This would be further developed in early postwar planning, subject of the next thread.

Transit to Wright-PattersonModern day Wright-Patterson has weak public transit connections. In the past the base was better served.

The base was adjacent to two mainline railroads, the Big Four and Erie, and the oldest parts of the bases were designed around railroad supply. Yet the more unusual transit connection is with interurban railroads.

The interurban line serving the base went under different names: Dayton, Springfield & Urbana, Ohio Electric, and Cincinnati & Lake Erie. This was the line used by the Wright Brothers to reach their flying field off the old Springfield Pike.

WWI era Patterson Field (at that time Wilbur Wright Field) and Fairfield Air Depot was served by Ohio Electric, which provided freight as well as passenger service to the base, actually coming on base via a branch line. Since the base was a flying school, presumably there was a lot of passenger traffic into Dayton when the student flyers had weekend leave.

The line was relocated along with Springfield Pike and the mainline steam railroads as part of the Conservancy district work on Huffman Dam, but remained in service up to 1940.

The 1927 Wright Field construction actually did make provision for passenger rail service via its gate construction, designing one of the gate-houses into a waiting room for the train, documented via this HABS/HAER drawing.

A big what-if is what if the interurban survived into the wartime era. The experience of the Chicago North Shore line was that wartime boom in passenger traffic (due to gas and tire rationing) kept the line alive into the postwar era, until it finally abandoned service in the early 1960s.

What makes the North Shore somewhat equivalent was that it had a close connection with the Great Lakes Naval Training Center, and, like the CL&E and Wright-Patterson, had a station on post, used by Navy personnel, especially for weekend liberty to Chicago or Milwaukee.

The North Shore had a fairly good commuter trade, too, which was enough to sustain the road well into the postwar suburban boom.

With the demise of CL&E there was still a transit need during wartime. The CL&E franchise was converted into bus operations, and it was a bus line that provided wartime commuter service to Wright and Patterson Fields, Riverside, and Fairborn.

Anecdotal evidence indicates bus service continued into the postwar era. The Dayton end of the line was at the former interurban station at 3rd & Patterson, which was torn down and rebuilt as this streamlined bus station, with bus parking to the side and maybe rear (this was also a good walkable location for people living out east but working in the Webster Station industrial area)

So a bit ironic that a relic of the wartime Wright-Patterson and Fairborn experience...taking the bus to and from the base and eastern suburbs… is actually in downtown Dayton.