Thursday, July 23, 2009

Daytonology Two Year Anniversary

Back in January there was this post, announcing yer humble hosts impending departure from Dayton and the closure of this blog.

The move is on hiatus due to the dire job situation but the blog is done. Daytonology has been running on empty for quite a while now, so this two year anniversary (the first posts were during July 2007) is as good a time as any to close the blog. Two to three years is the average life span of a blog, too.

Since there are things linking here the blog will be online for a few more months. This will give people who surf in time to remove links if they have any (if other bloggers are like me they periodically check their link roll and cull dead links).

Come December the delete button will be pushed and this blog will finally disappear into the ether.

Sunday, July 19, 2009

The Space Race is Over

Since this is the 40th anniversary of the first men on the moon, a good song on the subject, sort of, by UK folk-rocker Billy Bragg. Bragg was a fan of Simon and Garfunkle as a teen before going through the "cleansing fire of punk" (as he says) and one can tell the influence of a certain Paul Simon song here. In fact Bragg cribbed a line from it for this lyric. Y'all can guess that song.

Anyway, a good song from one of Billy Braggs best albums:

The Space Race is Over

When I was young I told my mum

I'm going to walk on the Moon someday

Armstrong and Aldrin spoke to me

From Houston and Cape Kennedy

And I watched the Eagle landing

On a night when the Moon was full

And as it tugged at the tides, I knew deep inside

I too could feel its pull

I lay in my bed and dreamed I walked

On the Sea of Tranquillity

I knew that someday soon we'd all sail to the moon

On the high tide of technology

But the dreams have all been taken

And the window seats taken too

And 2001 has almost come and gone

What am I supposed to do?

Now that the space race is over

It's been and it's gone and I'll never get to the moon

Because the space race is over

And I can't help but feel we've all grown up too soon

Now my dreams have all been shattered

And my wings are tattered too

And I can still fly but not half as high

As once I wanted to

Now that the space race is over

It's been and it's gone and I'll never get to the moon

Because the space race is over

And I can't help but feel we've all grown up too soon

My son and I stand beneath the great night sky

And gaze up in wonder

I tell him the tale of Apollo And he says

"Why did they ever go?"

It may look like some empty gesture

To go all that way just to come back

But don't offer me a place out in cyberspace

Cos where in the hell's that at?

Now that the space race is over

It's been and it's gone and I'll never get out of my room

Because the space race is over

And I can't help but feel we're all just going nowhere

Urban Bohemia and Left Wing Political Style

Stadt luft macht frei, City air makes one free.

This old German saying, perhaps coming from the Middle Ages or Renaissance, could be the theme of a cultural tendancy of modern America, too, as it is so contrary to the American ethos, which is, at heart, anti-urban. As we here in the Dayton region know all too well.

That cultural tendancy is for cultural and political free thinkers and innovators to seek out the city as a favorable mileau for innovation, leading to the formation of urban bohemia, but also the ongoing connection of this bohemia to a left politlcal turn, meaning either revolution or reform, either socialist or anarchist.

This phenomenon was perhaps already visible at the dawn of Bohemia, in 19th century Paris.

Bohemia & The Paris Commune

Bohemia was first named by Henry Murger, staging a play on Bohemia in 1849 and later publishing Scenes de la Vie de Boheme in 1851, just after the 1848 revolution, the one that overthrew Louis Phillipe. It's unclear what role Murgers bohemians played in that revolution. In fact it appears that Bohemia was pretty much apolitical at first. Yet it's certain members of the bohemian subculture participated in the great proleterian insurrection of 1871, the Paris Commune.

Perhaps that is a bohemian in the red coat, on the right of the above illustration of the Communards marching with Marianne, symbol of the French Revolution. Both literary figures of Parisian bohemia and at least one artist, Gustave Courbet, participated in the Paris Commune.

And this wasn't "left wing political" style, as over 20,000 died or were executed, with even more deported the colony of New Caledonia. Observers hostile to the Commune noted that it was "the death of Bohemia".

Another time and place where urban bohemia (and when isn't it urban?) intersected with politics, or at least social criticsm, was in Berlin, perhaps during the Wilhelmine era but certainly after 1918 with the coming of the Weimar Republic. This was most clearly seen with Berlin manifestation of the Dada movement. Dada was essentially apolitical in its original form in Zurich, but took a decidely left wing turn in Berlin, with artists such as the painter/illustrator Georg Grosz and collagist John Heartfield creating bitter, politcally charged artworks. It must be said that Grosz himself was no follower of any political line, distrusting ideology and political supermen, as he makes clear in his excellent autobiography: Ein klienes Ja und ein grosses Nein (A small Yes and a big No)

The Political Turn in American Bohemia

The first urban bohemia in the United States was probably Greenwich Village, which became a location for artists and writers in the early 20th century (perhaps earlier?). The development of the Village as an artists enclave parallelled the great "second immigration" to America from eastern and southern Europe and the second wave industrialization.

Artists of this era documented and even celebrated this booming urban world, especially artists of the "Ash Can School". One of these was John Sloan, one of the great painters of the American city, as demonstrated by this wonderful painting of a part of New York. Greenwich Village was also a center of political and social creativity. An example of this was The Masses, a magazine put out by the Village creative class. In the example below the same John Sloan who did the above painting provided this cover on the miners strike in Ludlow, Colorado (later immortalized in the Woody Guthrie song "The Ludlow Massacre").

Greenwich Village was also a center of political and social creativity. An example of this was The Masses, a magazine put out by the Village creative class. In the example below the same John Sloan who did the above painting provided this cover on the miners strike in Ludlow, Colorado (later immortalized in the Woody Guthrie song "The Ludlow Massacre"). The Village tradition of politically committed artists, writers, and illustrators lived on into our times. A good example is World War 3 Illustrated, a collection of comix and illustrations put out by people associated with the East Village scene, such as Eric Drooker and Peter Kuper, The East Village was a modern geographical and cultural expansion of the old Greenwich Village of The Masses and Ashcan School.

The Village tradition of politically committed artists, writers, and illustrators lived on into our times. A good example is World War 3 Illustrated, a collection of comix and illustrations put out by people associated with the East Village scene, such as Eric Drooker and Peter Kuper, The East Village was a modern geographical and cultural expansion of the old Greenwich Village of The Masses and Ashcan School. This same East Village scene was the setting for the popular musical Rent.

This same East Village scene was the setting for the popular musical Rent.

One doesn't usually associate musicals with either bohemia or political content, but Rent is perhaps the exception. The story of Rents relation to 19th century Paris via Puccini is probably known to readers thus need not be detailed here. What is probably not known is that the writer/composer Jonathan Larson was himself quite political, having developed an earlier musical on the right wing ascendence in 1980s America. And Larson pretty much lived the bohemian life of little money and day jobs, concentrating on his art.

And of course there is that theme of AIDS running through the musical. In fact one thing that made Rent radical was it's putting of gay and lesbian relationships on equal footing as straight ones.

Urban bohemia had long provided cover for sexual innovators and non-standard relationships, so became a tolerant mileau for gays and lebsians. One of the sources of modern gay rights movmenet came out of the Greenwich Village bohemia, the explicitly political Gay Liberation Movement.

Art and politics were to cross again with the advent of AIDS and the hostile social and political climate the disease engendered. One response was via the work of artists like Keith Haring, part of the street art scene, and the edgier David Wojnarowicz, who went beyond art and fought legal battles in the culture war against the right wing. Haring was already well known in art circles for his graffitti-inspired work when he joined the new ACT-UP movement. ACT UP is a good example of the politicl potential of a radicalized creative class. In this case it was not just artists but individuals involved in commercial art, the adverstising industry, who developed a potent visual identity for the movement, which was innovative in agit-prop tactics, civil disobedience, and media manipulation.

Haring was already well known in art circles for his graffitti-inspired work when he joined the new ACT-UP movement. ACT UP is a good example of the politicl potential of a radicalized creative class. In this case it was not just artists but individuals involved in commercial art, the adverstising industry, who developed a potent visual identity for the movement, which was innovative in agit-prop tactics, civil disobedience, and media manipulation. This continued on into non-gay alternative politics, probably best known via the anti-globalization demonstrations in Seattle, but also via the Indymedia/Infoshop movement, which is probably more anarchist than left (if one had to put a label on all this).

This continued on into non-gay alternative politics, probably best known via the anti-globalization demonstrations in Seattle, but also via the Indymedia/Infoshop movement, which is probably more anarchist than left (if one had to put a label on all this). New York has been mentioned a lot. But urban bohemias exist outside of NYC. Particularly on the West Coast, but also here in the Midwest, in Chicago.

New York has been mentioned a lot. But urban bohemias exist outside of NYC. Particularly on the West Coast, but also here in the Midwest, in Chicago.

Chicago had it's own Greenwich Village in Tower Town, the neighborhood directly west of the old Water Tower, around Bughouse Square (traditionally the Speakers Corner of Chicago), an intersection of the political, literary, and artistic (as can be seen by this collection on Chicago's free speech tradition. Frequently seen in that collection is the Dill Pickle Club, which rang the same politico-cultural changes as Greenwich Village.

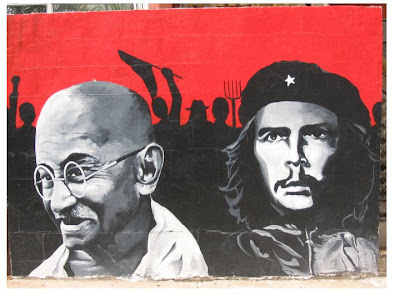

Chicagos politicized bohemian spirit continues one in modern things, like some of the plays of Theatre Oobleck. And some of the newer neighborhoods, which are described as "hipster" but also have a certain political turn, as one can see by these pix of a mural on various freedom fighters, in the traditional colors of anarchy and revolution, red and black.

The Mexican revolutionary Zapata Bob Marley and some woman who I don't recognize.

Bob Marley and some woman who I don't recognize.

An odd juxtaposition, Ghandi and Che Guevera. Could they be any more different in style?

Dayton Bohemia and Left Wing Political Style

Yer humble host wouldn't know because, though a longtime lefty in spirit, he's not part of the local bohemia. Since the scene here is more music based one won't see (or hear) much politics because, unlike in Europe, the US alt/indy scene isn't that political. Yes, the left does have the best music, but its usually the British left.

Locally, if there is a political turn it's more of a libertarian one, or indifference to politics (which is the usual image of the bohemian, someone who lives for art)

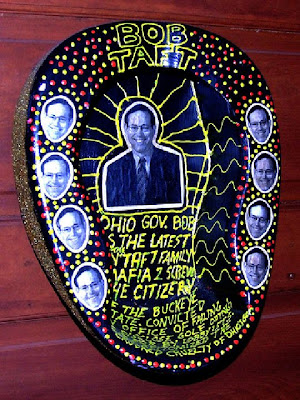

About the only local artist that works political content into his work is Drexel Dave Sparks, though he's probably more a libertarian than a lefty (based on his previous incarnations online as Sparkdog, host of the late, lamented Fat City News). An example of DD's political content; bedpan commentary on Bob Taft:

I recall one other local visual artist (whos name escapes me, but I do know he is an Iraq veteran) who's done some interesting things on the Iraq War and related themes. And there is a fellow associated with The Circus who does rap/spoken word with some proto-political content..more about social conditions...which have political implications.

And that's about it for Dayton. Which brings up the the fact that this political turn in urban bohemia is probably found only certain large cities. Yet it neglected aspect of the creative class concept, which tends to depoliticize the cultural creative scene, rather than recognize a bohemian tendancy to political radicalism, or, at very least, political critique.

Mock Turtle Press

More signs of life in the dying city.

Stopping by Jazzy Java Cafe I happened across a basket of little chapbooks with a donation can. Entitled "Collage" this is a collection of stories. The one bought was "short stories by Dayton authors". So it seems people are still doing zines here.

The publisher is "Mock Turtle Press", who maintains both a facebook and myspace page. Here's a link to the hipper myspace site (and, as is usual, the "Freinds" section provides linkage to local cultural creatives and their freinds and associates).

Perhaps what's interesting here is the concept of mixing print & paper (zines) with a presence in the social networking online world. The myspace/facebook sites promotes the zine, but one wonders if a zine could work the other way, promoting a blog or online place.

Stuff like this is heartening; small shoots of independent cultural production in a desert of soul sucking cultural conformity and conservativism. It's the small thrills of looking at the little postcards and mini-flyers at, say, Gem City or Jazzy Java or that coffeeshop at Paccia, or at the 5th Street Deli (and the larger band and event posters in the windows); that there are things happening out there, a scene of sorts creating and producing things, usually music but other types of cultural activity, too.

In short, a local bohemia or alternative scene.

Perhaps Dayton could evolve something like the Bristol Underground Scene. Or maybe it already has and all is needed is a wikipedia entry?

The Dayton Daily News Beats the Creative Class Drum

Daytonology has done some desultory blogging about Richard Florida's Creative Class concept and the local attempt at doing Creative Class things, the Dayton Create initiative.

But not too much because yer humble host isn't part of this class, or category. Not because of cynicsm since Florida is on to something (albeit something difficult to measure).

What's good to see is the Dayton Daily News continuing to report on the progress and the positive editorials on the intiatives. Recently there was one on UpDayton, the young adult group, who have been quite active: Creative Class Living Is Up to Name

The article mentions the "summit" sponsored by UpDayton, which came in for quite a bit of critique from the local blogosphere (Daytonology Included):

One group organized a summit last spring where two hundred or so people showed up to mull over what to do first. What could have been a boring, discouraging gripe fest was a mass brainstorming session that wrapped up with participants settling on four big things to tackle.

...oddly enough the DDN itself is the source of the regions' largest ongoing "boring, discouraging gripe fest"; the readers comments to their local news articles, especially ones dealing with urban affairs.

I guess this editorial signals that the editors do not share the views of their more vocal readers.

The editorial discussed UpDayton's "Don't Dog Dayton" video contest, which is one of three things they are pushing for in their Grow Downtown intiative. Another is revitalize existing festivals, which are, presumably, not attractive to the 20 and 30 - somethings (one of the local bloggers has noted the festivals decline, so a definite issue here).

It will be easy for UpDayton and the other DaytonCreate initiatives to get lost in the generalized malaise and negativity, the black hole of bad local karma, so a big pat on the back for the DDN for keeping this (admittedly small) counter-trend in public view via their editorials.

Saturday, July 18, 2009

Building Xenia Junction.

Xenia developed into one of Ohio’s railroad towns, a species of place that had some importance to railroading due to repair facilities and as a junction point for the railroads that criss-crossed Ohio during this era.

On the map this looks quite confusing, so this post will attempt to untangle the knot of railroads via a chronology.

The story starts with a pioneer railroad, one of the very first in the state. The Little Miami Railroad reached Xenia in 1845, five or six years before Dayton received it’s first railroad. The early lines didn’t have powerful engines, so grade was a consideration. One can see this in the Little Miami right-of-way; The Little Miami took a valley route into Xenia, departing the Little Miami bottomlands at Spring Valley and following the valley of Gladys Run into town: The Little Miami Railroad, entered town on the exceptionally wide Detroit Street (on the east side of the street), which was a bit unusual for Ohio (there are at least two examples of this in Kentucky, in Frankfort and Lagrange).

The Little Miami Railroad, entered town on the exceptionally wide Detroit Street (on the east side of the street), which was a bit unusual for Ohio (there are at least two examples of this in Kentucky, in Frankfort and Lagrange).

Xenia railroad lore says that a promoter donated a building on Detroit Street as a station, with the proviso that trains would stop there for all time. And apparently passenger trains did continue to stop there after the union station was built in the 1850s.

Next a few diagrams showing the evolution of the junction.

Xenia, starting with the Little Miami. In the mid 1840s Columbus had no railroads, so a daily line of mail stages went into operation between the railhead at Xenia and Columbus and Dayton.

In the mid 1840s Columbus had no railroads, so a daily line of mail stages went into operation between the railhead at Xenia and Columbus and Dayton.

The next year the line was extended to Springfield. The original route was to be via Clifton and it’s big mill, but the promoters of Yellow Springs offered money to route the line through that town. The route via a mill might have been because the railroad was initially conceived, in part, to provide an outlet for the merchant millers of the Little Miami valley.

At Springfield one took a stage to make the connection with the Mad River Railroad railhead at Bellefontaine. There was also a line of “daylight stages” to connect with Columbus, perhaps via the National Road. The journey from Cincinnati via Xenia, Springfield, stage coach to Bellefontaine, overnight in Bellefontaine, then on to the lake port of Sandusky took around 27 hours in 1847.

The next line was the Columbus and Xenia, which presumably replaced the stage to Columbus. This line would eventually connect with the Columbus and Cleveland railroad, and ultimately to the eastern seaboard via the Lake Shore Railroad east from Cleveland, becoming a main line into Cincinnati, relegating the old Little Miami north of Xenia to branch line status.

This line would eventually connect with the Columbus and Cleveland railroad, and ultimately to the eastern seaboard via the Lake Shore Railroad east from Cleveland, becoming a main line into Cincinnati, relegating the old Little Miami north of Xenia to branch line status.

The C & X entered Xenia via the valley of one the forks of Shawnee Creek, joining the Little Miami in the valley just south of the forks of Shawnee. The Xenia junction was starting to form

The Columbus and Xenia had originally projected to connect to Dayton. Instead, a railroad was projected east from Dayton. This was the Dayton, Xenia and Belpre.

The DX&B was intended as a “resource road”, connecting the Hanging Rock Iron region (and early coal fields) to Dayton manufacturers, and also offering a connection to tidewater via the Baltimore and Ohio branch across the river from Belpre at Parkersburg.

This line was never completed. Grading extended as far as Jamestown and then work ceased.

In the 1870s there was a second attempt at a “coal road”, a narrow gauge line from Dayton to the vicinity of Wellston and Jackson in Appalachian Ohio. Narrow gauge is usually associated with logging and mining railroads out west, but here it was used as a long distance cross-country line.

This line was eventually converted to standard gauge and taken over by the Baltimore & Ohio.

Xenia Junction in Detail

This vignette shows the old 1850s two story union station. Union because it served more than one railroad at the time. These lines soon went under joint operation and eventually merged. Ultimately they were taken over by the great east-west railroads. In this case the Pennsylvania and Baltimore and Ohio.

The junction in the 1870s. One can see the station, a roundhouse, a freight house, and some sidings. By the 1890s one sees the Baltimore & Ohio branch swinging into the junction area, with its’ own depot. This is probably a fairly accurate track configuration for that era.

By the 1890s one sees the Baltimore & Ohio branch swinging into the junction area, with its’ own depot. This is probably a fairly accurate track configuration for that era.

Xenia Junction in the 1930s, from the air. This was the peak of railroading in Xenia, with various shop and support facilities, a small yard, and some sidings. One can see that structures from the 1850s, 70s, and 90s survived into the 1930s. The Greene County historical society has a collection of artifacts, photos, and a scale model of the junction, worth a visit for railfans and history buffs.

The same site today. All the railroads are gone and the junction is now a cycling center, with Xenia Station as a visitors center for bike trails radiating from Xenia on the old railroad right-of-ways.

Another view of the junction. The building is a reconstructed baggage station and railway express office, and has a small exhibit on railroading in Xenia.

And in this aerial one can see how the bike path follows the old Little Miami grade out of the valley to Detroit Street. Some surviving buildings are keyed from old maps to the aerial, showing how some of old Xenia survived into our time (although it should be noted that the station is a reconstruction).

It might be worthwhile taking a closer look at the Sanborn maps to how much of industrial Xenia has survived. Though it had good rail connections Xenia didn’t develop into an industrial center the way nearby Springfield did. And why that was is a good question for econmic history.

Another future post would be to investigate the development of the railroad system in south & west Ohio, since there might be an interesting economic geography story to be told. This would look at the rise of Cincinnati & Dayton as a railroad centers as part of the development of a regional network. Maybe more the subjec of a book or journal article than a blog post, though.